A57 Benko Gambit

declined – a practical weapon

GM Rainer Knaak

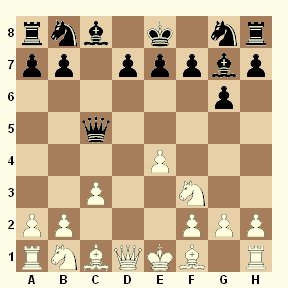

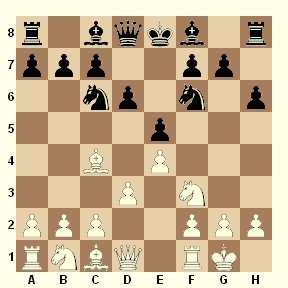

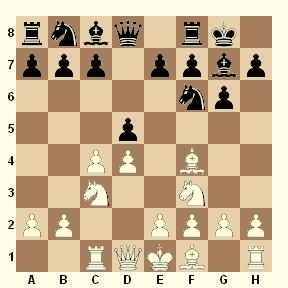

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 b5 4.Nf3 Bb7 5.Qc2

Actually,

my results against the Benko Gambit had never been particularly

good - until I had the idea of declining the gambit. At first I

did so with 4.cxb5 a6 5.b6. However, after 5...e6 some

difficulties occurred. Therefore, I changed to 4.Nf3, a kind of

waiting move, because after the most frequent reply 4...g6, I

could enter my favourite variation with 5.cxb5 a6 6.b6.

Actually,

my results against the Benko Gambit had never been particularly

good - until I had the idea of declining the gambit. At first I

did so with 4.cxb5 a6 5.b6. However, after 5...e6 some

difficulties occurred. Therefore, I changed to 4.Nf3, a kind of

waiting move, because after the most frequent reply 4...g6, I

could enter my favourite variation with 5.cxb5 a6 6.b6.

But the move most frequently played in practice is not always

the best. Instead of 4...g6 Black in turn can play a waiting

game with 4...Bb7, and statistically this is the continuation

which is clearly best for Black (only 53% for White). The first

player now has a number of options, but all have one

disadvantage (5.Nc3 - now the knight will be asked about its

intentions with 5…b4; 5.Nbd2 - leaves it unfavourably placed as

does 5.Nfd2; 5.Qb3 - a relatively successful surprise move, but

not really good; 5.a4 - after 5...Qa5+ 6.Bd2 b4 White's position

is unharmonious). My suggestion 5.Qc2, which prepares e2-e4,

also has a drawback: the queen no longer protects d5. Moreover,

on c2 it can more easily be attacked.

Thus, in the diagram position White will push through e2-e4 and

Black basically has only one sensible plan: he must quickly

attack the white centre. He can do so with 5...dxc4 6.e4 e6 but

after 7.Bc4 exd5 8.exd5 accepting the pawn sacrifice is not very

good, and after 8…Be7 the second player also gets a cramped

position.

In the diagram position more critical is 5…Na6!, after which

White has two options:

a) 6.a3 loses a tempo and after 6…bxc4 7.e4 e6 8.Bxc4 exd5

9.exd5 Nc7 Black has another piece directed against d5. My

analyses - unfortunately, there are not many practical examples

with this position - fail to prove a clear advantage for White,

but it is obvious that the second player has to solve a lot of

practical problems.

b) 6.Nc3 simply allows 6…Nb4; things now continue with 7.Qd1

bxc4 8.e4 and now 8…Nd3+ 9.Bxd3 cxd3 has almost always been

played. Though this gives Black the pair of bishops, it does not

compensate for the lack of space and development. Better is

8…e6!, when things get very tactical. First of all, Black can

answer 9.Bxc4 with 9…Nxe4!. After the better 9.Bg5 there follows

9…exd5 and White has to decide whether to play 10.exd5 or 10.e5.

In both cases, sometimes hair-rising complications occur and it

is not entirely clear how to judge the whole variation exactly

here either. At any rate, the player who knows his way better,

should have an advantage.

B27 Sicilian: Being optimistic with an

exposed queen

GM Dorian Rogozenko

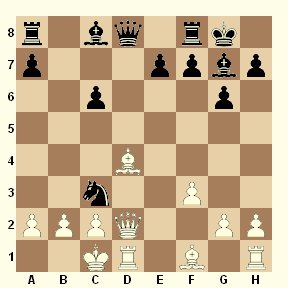

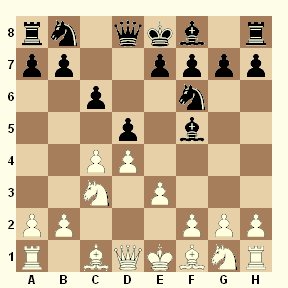

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 g6 3.d4 Bg7 4.dxc5 Qa5+ 5.c3 Qxc5

With the sequence

2…g6 3.d4 Bg7 Black usually intends to reach a Dragon setup,

while avoiding a couple of particularly dangerous variations,

e.g. after 4.Nc3 (the most popular move) 4...cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nc6

6.Be3 Nf6 White is neither able to reach the setup with 9.0-0-0

- see also the article by Andrй Schulz - nor is he able to reach

a proper traditional Yugoslav Attack (with 9.Bc4). One reason

for this is that Black can still play d7-d5 in one move (instead

of d7-d6 first and d6-d5 later as in normal Dragon lines).

With the sequence

2…g6 3.d4 Bg7 Black usually intends to reach a Dragon setup,

while avoiding a couple of particularly dangerous variations,

e.g. after 4.Nc3 (the most popular move) 4...cxd4 5.Nxd4 Nc6

6.Be3 Nf6 White is neither able to reach the setup with 9.0-0-0

- see also the article by Andrй Schulz - nor is he able to reach

a proper traditional Yugoslav Attack (with 9.Bc4). One reason

for this is that Black can still play d7-d5 in one move (instead

of d7-d6 first and d6-d5 later as in normal Dragon lines).

Rogozenko says about the line chosen by White: "4.dxc5 Qa5+ 5.c3

is considered to be one of the most promising continuations for

White and poses a problem for many Black players". However,

certainly for many Black players it is attractive that an

innocent player with White might rather tend to finish his

development, maybe with Be2, Bd3 or h3; after that Black has no

problems reaching a good position. It definitely helps that

White has also made a concession with c3. Thus, White is well

advised to become active immediately, and there are two

possibilities to do so, 6.Be3 and 6.Na3.

a) The consequence of 6.Be3 Qc7 is 7.Bd4 Nf6 8.e5, but this

initiative very quickly vanishes. Rogozenko now proposes 8…Nh5

(8…Ng4 has also stood the test) and writes: "A detailed

consideration of this position will reveal the following

favourable factors for Black: The knight temporarily parked on

h5 does is in no danger of being lost, because the square f4 is

available to it; the bishop on d4 is vulnerable and White will

most likely have to exchange it for one of the black knights;

after ...f7-f6 White will not be able to maintain control over

e5 and the second player will have two potentially powerful

pawns in the centre, where most of the black pieces will quickly

exert considerable pressure. All this lets us conclude that

Black's chances are by no means worse in the ensuing sharp

struggle".

b) More subtle is 6.Na3, after which follows 6…Nf6. Then the

most dangerous move is 7.Nb5, after which Rogozenko favours

7…b6, the reason: "Now the queen can retreat to b7 if need be.

This might appear somewhat artificial but anyway the move ...b6

is part of Black's plan". Now, a long forced variation runs as

follows: 8.e5 Ng4 9.Qd4 Nxe5 10.Qxc5 Nxf3+ 11.gxf3 bxc5 12.Nc7+

Kd8 13.Nxa8 Bb7. Dragon players will be thrilled because the

material balance is similar to typical Dragon endgames. Black

has a pawn for the exchange, added to which are doubled white

pawns, this time on the f-file. (RK) {B27 Sicilian 2...g6}

B76 Sicilian: Breathing life into the Dragon: The

Bjerring-Variation

B76 - Dracon (By

Andrй Schulz)

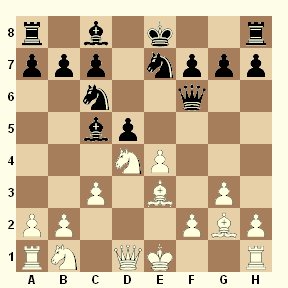

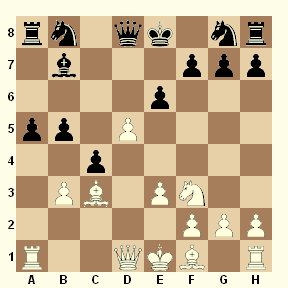

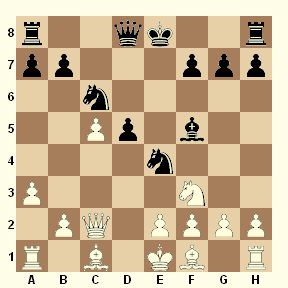

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 g6 6.Be3 Bg7 7.f3

0-0 8.Qd2 Nc6 9.0-0-0 d5 10.exd5 Nxd5 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.Bd4 Nxc3!

Today, the

biggest problem for Dragon players is the variation with

9.0-0-0. It turned out that refraining from 9...d6-d5 simply

gives White good attacking chances on the kingside. After 9...d5

10.exd5 Nxd5 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.Bd4 the continuation 12...e5 13.Bc5

became the main line, but the positional deficit of the worse

pawn structure has long-term effects and most players will

definitely not like to play like this with Black.

Today, the

biggest problem for Dragon players is the variation with

9.0-0-0. It turned out that refraining from 9...d6-d5 simply

gives White good attacking chances on the kingside. After 9...d5

10.exd5 Nxd5 11.Nxc6 bxc6 12.Bd4 the continuation 12...e5 13.Bc5

became the main line, but the positional deficit of the worse

pawn structure has long-term effects and most players will

definitely not like to play like this with Black.

Therefore, the author suggests 12...Nxc3! The first game with

this move was Iskov-Bjerring from 1974 and this is why Andrй

Schulz proposes the name Bjerring-Variation. The follow-up

involves a pawn sacrifice: 13.Qxc3 Bh6+ 14.Be3 Bxe3+ 15.Qxe3

Qb6! 16.Qxe7 Be6 and now 17.Qa3 has established itself as the

best and most often played move:

Black players learned to play this position (right) in the hard

way. At first, they tried 17...a5, followed by 18...Qb4, but

White used the time to put his bishop on e4. Then people

switched to 17...Qf2, which might not be that bad and is the

second choice of the author. After that 17...Rfd8 appeared on

the scene - which seems logical, as the other rook may well want

to go to b8. Only after the game Kasparov-Topalov, Amsterdam

1995, - unfortunately the only one on such a high level - was

17...Rad8! suggested - by Kasparov himself. Since then this move

has been played with success though one does not feel that its

consequence - White is not able to obtain any advantage here -

has been fully understood by all players. Schulz assumes: "Probably

the line has been underrated until now because of psychological

reasons: What Dragon player wants to swap his Bg7 voluntarily?

However, even without its virulent guard on g7 Black's position

on the kingside proves to be surprisingly robust". (RK)

C11 French: Blindfold discovery by

Morozevich

GM Evgeny Postny

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.e5 Nfd7 5.f4 c5 6.Nf3 Nc6 7.Be3

a6 8.Dd2 b5 9.a3 g5

In

the variation with 7...a6 and 8...b5 to counter the Steinitz

System with 4.e5, things do not look good for Black: according

to current theory White is simply better. 9...g5, as dreamed up

by Morozevich, would, if it's any good, be very helpful;

possibly White would then have to switch back from 9.a3 to

9.dxc5.

In

the variation with 7...a6 and 8...b5 to counter the Steinitz

System with 4.e5, things do not look good for Black: according

to current theory White is simply better. 9...g5, as dreamed up

by Morozevich, would, if it's any good, be very helpful;

possibly White would then have to switch back from 9.a3 to

9.dxc5.

But this is not yet the case. First of all, what makes one think

is that Morozevich did not reveal his discovery in an important

tournament but in a blindfold game. Nevertheless, a few players

have followed his lead, even Bareev, Nakamura, Roiz and Volkov.

First, Postny shows that Black need not fear the sidelines with

10.dxc5, 10.Nxg5 and 10.f5. Then he turns to the main line with

10.fxg5 cxd4. Here 11.Bxd4 did not prove its worth, even though

it was played by Anand (though in the blindfold game mentioned

above) and Carlsen. White has difficulties defending the e5-pawn

and Black gets a healthy position.

White did much better with 11.Nxd4 Ncxe5, both encounters with a

high Elo-average ended 1-0. But in all the games Postny has

improvements to offer for Black, e.g. he believes that Bg7 and

0-0 should be played first.

But the latest word in this variation is the discovery 10.Ne2!.

This knight was not particularly well placed on c3, and now it

is heading for the black squares d4 and f4, or, of course, g3.

In the stem game Cvek-Akobian, Turin ol (Men) 2006 [The game was

also treated in the column 'Move by Move 113' by Daniel King],

there came 10...g4 11.Nfg1 f5 12.h3 and White already had the

better prospects. Postny thinks that 10...gxf4 is rather more in

the spirit of the line. He adds an extensive analysis of this

alternative move but comes to the conclusion that Black has no

clear way to equality.

I still see room for improvements. If you play 10...g4 11.Nfg1,

you absolutely have to follow up with 11...f6 (Fritz9). But

maybe White even then is able to maintain his centre to keep the

better position. After 10...gxf4 11.Bxf4 the analyzed move

11...cxd4 falls in with White's plans because the Ne2 is not

well placed. A useful waiting move such as 11...Bb7 deserves

consideration. At any rate, one has to agree with Postny that it

is too early for a final judgment and that we can expect a

plethora of interesting games. (RK)

C45 Scotch with 7.g3 – quiet,

positional play

IM Hazai, GM Lukacs

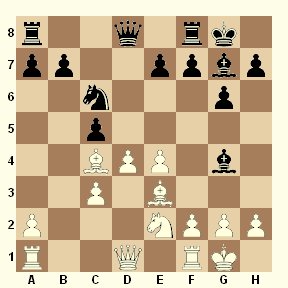

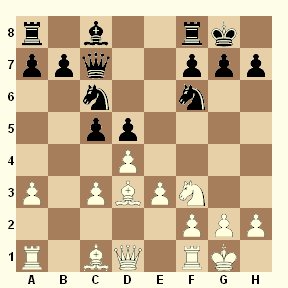

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 exd4 4.Nxd4 Bc5 5.Be3 Qf6 6.c3 Nge7

7.g3 d5 8.Bg2

In CBM 113 we

published an article about 6.Nb5?!, but of course 6.c3 Nge7 is

the traditional continuation. Actually, 7.Bc4 is now the main

line, but 7.g3 has been at least as successful; it is used by

strong players, and so far there is not much theory. With 7...d5

Black makes use of the fact that White has done nothing to

control the central square; after 8.Bg2 we reach the diagram

position above.

In CBM 113 we

published an article about 6.Nb5?!, but of course 6.c3 Nge7 is

the traditional continuation. Actually, 7.Bc4 is now the main

line, but 7.g3 has been at least as successful; it is used by

strong players, and so far there is not much theory. With 7...d5

Black makes use of the fact that White has done nothing to

control the central square; after 8.Bg2 we reach the diagram

position above.

Black can simply take on e4 and try to equalize the game. Or he

takes on d4 to give White an isolated pawn.

a) After 8...dxe4 White has often played 9.0-0, when the game

can still transpose into various lines. The aggressive 9.Nb5

also comes into consideration, and with 9.Nd2 White can head for

a solid position. Emil Sutovsky, who has very successfully

employed the setup with 7.g3, has always played 9.0-0 first.

b) With 8...Bxd4 Black wants to block the isolated pawn arising

after 9.cxd4 dxe4. White replies 10.Nc3 and now there are two

little tricks; after 10...0-0 White delays taking on e4 by

playing 11.0-0, and now in some lines the bishop takes on e4. If

Black plays 10...Bf5, then 11.d5 is aggressive and strong.

c) 8...Nxd4 also intends to leave White with an isolated pawn.

After 9.cxd4 Bb6 the authors recommend 10.Nc3; a possible

continuation is 10...dxe4 11.Nxe4 Qg6 12.0-0 0-0 13.Nc5

and now in Sutovsky-Harikrishna, Pune 2004, an almost completely

balanced position arose (in the game 8...dxe4 9.0-0 etc. was

played). It seems as if in all lines Black never completely

equalizes but sometimes White's advantage is rather symbolic

than real.

C55 Giuoco Piano: Avoiding symmetry

GM Mihail Marin

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Nf6 4.d3 h6 5.0-0 d6

Didn't we already learn

as children that moving the h- or the a-pawn should be avoided

at an early stage in the game? At the beginning, the author

explains how this setup arises. Black wants to fianchetto his

Bf8 and therefore wants to play ...g6. But the immediate 4...g6

is countered with 5.Ng5. Therefore 4...h6, and now White's main

answer is 5.0-0. Now follows another preparatory move with

5...d6 because 5...g6 could be countered with 6.d4!.

Didn't we already learn

as children that moving the h- or the a-pawn should be avoided

at an early stage in the game? At the beginning, the author

explains how this setup arises. Black wants to fianchetto his

Bf8 and therefore wants to play ...g6. But the immediate 4...g6

is countered with 5.Ng5. Therefore 4...h6, and now White's main

answer is 5.0-0. Now follows another preparatory move with

5...d6 because 5...g6 could be countered with 6.d4!.

How does White react now? According to Marin, only a

counterthrust in the centre comes into consideration, but not

the immediate 6.d4 because of 6...Bg4! Neither does 6.Nc3

threaten anything dangerous, even more so because the as yet

untried 6...Na5 is a strong option. Best is to prepare d3-d4

with 6.c3 or 6.Re1.

An important position for the evaluation of the whole system

arises after the moves 6.c3 g6 7.d4 Qe7 8.Re1 Bg7 9.Nbd2 0-0

10.h3:

Marin: "Black is now at a crossroads. He has built up a solid

position but it is not easy to develop counterplay against

White's strong centre". Thus 10...Nh7 11.Nf1 Ng5 failed to prove

its value because Tiviakov's 12.Bxg5!? hxg5 13.Ne3 is rather

awkward for Black. Another move is 10...Qd8, intending ...exd4

and ...d6-d5. Though Black in practice has done well with this,

our author mistrusts the "slightly paradoxical queen retreat".

The most often played and natural move is 10...Bd7. After the

logical continuation 11.Nf1 Rae8 12.Ng3 Marin suggests 12...Kh8,

because Vladimir Malaniuk played like this (after having chosen

12...a6 earlier). In fact, it's always a good method to look at

the games of a specialist in a variation. The function Reference

in ChessBase 9.0 is a great help here. Other moves in Black's

setup can be: Qd8, a6, Bc8, Nh7 and possibly h5. The author

considers that the system is completely sound. (RK)

D10 Slav Defence: The Wojtkiewicz

Variation

GM Eric Prie

1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.e3 Bf5

The

diagram position already occurred in a game by Steinitz in his

World Championship match against Zukertort. The variation was

also discussed in Alekhine-Capablanca, New York 1924. About the

name the author writes: "The recently departed

Latvian-Polish-American Grandmaster was the world specialist in

this line, with which he achieved enviable statistics in an

overall environment of unfavourable figures for Black."

The

diagram position already occurred in a game by Steinitz in his

World Championship match against Zukertort. The variation was

also discussed in Alekhine-Capablanca, New York 1924. About the

name the author writes: "The recently departed

Latvian-Polish-American Grandmaster was the world specialist in

this line, with which he achieved enviable statistics in an

overall environment of unfavourable figures for Black."

The author first deals with the motives leading to the diagram

position. The first player obviously first of all wants to avoid

the main line Slav (4.Nf3 dxc4), because Black players, who want

to play this variation, are no longer keen on the Semi-Slav (that

is 4...e6) or the Schlechter Defence (4...g6). Then GM Prie

refutes a couple of sidelines, such as e.g. 5.cxd5 cxd5 6.Qb3

Qb6?, after which follows 7.Nxd5 Nxd5 8.Qxd5, and now e.g.

8...Qb4+ 9.Kd1!

Finally he reaches the main line 5.cxd5, with which White scores

72% - another proof of how misleading statistics can be. After

5...cxd5 6.Qb3 Bc8! we reach the actual starting position of the

variation. Superficially seen, White seems to have a slight

advantage because of his slightly better development. But the

structure of a Slav Exchange does not leave much room to exploit

such an advantage. It is difficult to say what the critical line

is. Many White players cannot resist the temptation and move the

f-pawn, immediately or after first playing Nf3-e5. For instance,

7.Bd3 Nc6 8.f4 e6 9.Nf3 Be7 10.0-0 0-0 11.Ne5 Nd7!

The move with the knight is absolutely necessary, Black is close

to equality. (RK)

D31 Semi-Slav: Noteboom not booming?

GM Dorian Rogozenko

1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.Nf3 e6 4.Nc3 dxc4 5.e3 b5 6.a4 Bb4 7.Bd2 a5

8.axb5 Bxc3 9.Bxc3 cxb5 10.b3 Bb7 11.d5 (Nf6 12.bxc4 b4

13.Bxf6 Qxf6 14.Qa4+ Nd7 15.Nd4 e5 16.Nb3 Ke7 17.Be2)

Actually, the

Noteboom system has a good reputation and is even one of the

reasons why some White players turn to 4.e3. However, once you

have on the board, the position after the fourth move you have

to go along with playing the sharp lines.

Actually, the

Noteboom system has a good reputation and is even one of the

reasons why some White players turn to 4.e3. However, once you

have on the board, the position after the fourth move you have

to go along with playing the sharp lines.

If you are startled by the fact that the theory extends up to

move 24 I can reassure you: From move 8 to 17 Black can

basically play only forced moves (whereas White has the more

often played alternative 11.bxc4 at his disposal).

Only then does Rogozenko's introductory text divide: Black has

17...Rhc8 and 17...Qd6.

a) After 17...Rhc8 18.0-0 Nc5 19.Nxc5 Rxc5 20.f4 e4 the position

is closed; Rogozenko now recommends 21.Qd1, which so far has

been played in only one game (Naumann-Galkin, Yerevan 1999).

After the move played in the game 21...Kd6? White could have

secured a big advantage with 22.Qb1!, after other moves 22.Qd4

is a good option.

b) ChessBase author Michal Krasenkow not only introduced

17...Qd6 into practice, he also scored a couple of fine

successes with it. Now 18.f4 turned out to be the best reply,

after which 18...Rhc8 19.0-0 Nc5 20.Nxc5 Rxc5 leads to the next

diagram position:

Now in some games there came 21.Rad1, followed by Qa1-e5, but

Krasenkow has shown that Black's passed pawns are rather faster

in the endgame.

Rogozenko suggests 21.Rf3 and analyses this move extensively. To

prevent the doubling of rooks on the f-file, the answer is

21...e4. Things might continue like this: 22.Rh3 h6 23.Rh5 f6

24.Qc2 and White's attack is faster than the black pawns.

If everything is correct, the fans of the Noteboom system do

have a problem. (RK)

D89 Grьnfeld Defence: The exchange

sacrifice – not dangerous after all

GM Michal Krasenkow

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.cxd5 Nxd5 5.e4 Nxc3 6.bxc3 Bg7

7.Bc4 c5 8.Ne2 0-0 9.0-0 Nc6 10.Be3 Bg4 11.f3 Na5 12.Bd3

cxd4 13.cxd4 Be6 14.d5 Bxa1 15.Qxa1 f6

Once White has

decided to enter the exchange variation with 7.Bc4, it is not so

easy for him to avoid the diagram position: 12.Bxf7+ (Seville

Variation), 14.Rc1 (a pawn sacrifice), 14.Qa4 (a loss of time,

allowing a6 followed by b5) - all these moves are not really

convincing.

Once White has

decided to enter the exchange variation with 7.Bc4, it is not so

easy for him to avoid the diagram position: 12.Bxf7+ (Seville

Variation), 14.Rc1 (a pawn sacrifice), 14.Qa4 (a loss of time,

allowing a6 followed by b5) - all these moves are not really

convincing.

About the diagram position the author has the following to say:

"The critical position, which has been at the centre of more or

less intensive discussions for almost 60 years. It's amazing to

see some lines, once buried, re-emerging 50 years later, with

improvements found."

Indeed, White has a large number of moves to choose from on his

16th move and fashion has occasionally brought old moves with

new variations back into the centre of attention. Most of these

moves are treated with one important game as an example.

The largest section is dedicated to 16.Bh6, a move, which

Bronstein already played in 1950. Back then, the weaker

16...Qb6+ was played, whereas later 16...Re8 was taken for

granted. White then has a number of promising options, but

17.Kh1 Rc8 18.Nf4 Bd7 19.e5 Nc4 20.e6 Ba4 has been played most

often:

The piece sacrifice 21.Nxg6 fxg6 22.Bxg6 has been analysed to a

draw.

The last variation Krasenkow looks at is 16.Qd4, a move, with

which Loek van Wely won in Dortmund 2005 against Sutovsky. But

here too, the most recent analyses show that Black can at least

reach an equal game.

Playing with Black you have to know a lot of variations,

therefore the author writes: "A good memory (knowledge of the

most important variations), a sense of dynamics and keen

tactical vision decide the outcome of the game." (RK)

D92 Grьnfeld Defence: A rich variation

GM Lubomir Ftacnik

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5 4.Nf3 Bg7 5.Bf4 0-0 6.Rc1 dxc4

Here

two different concepts clash: Black does everything to castle

quickly and he does give up the centre; White gathers all his

forces around this centre, and he is not in a hurry to castle.

Now a decision has to be made - 7.e3 or 7.e4. Both moves are

extensively analysed in the database and lead to completely

different positions and thus we actually have two articles.

Here

two different concepts clash: Black does everything to castle

quickly and he does give up the centre; White gathers all his

forces around this centre, and he is not in a hurry to castle.

Now a decision has to be made - 7.e3 or 7.e4. Both moves are

extensively analysed in the database and lead to completely

different positions and thus we actually have two articles.

a) 7.e3 seems to be a very careful move because the pawn on d4

is now firmly protected. After 7...Be6 the quiet play with a

chance for a slight advantage is over, 8.Ng5 is necessary. Now

8...Bd5 9.e4 h6 10.exd5 hxg5 11.Bxg5 Nxd5 12.Bxc4 Nb6 13.Bb3 Nc6

14.Ne2 leads to a rather unconventional position, in which White

has scored quite well. According to Ftacnik Black should play

14...a5, "with good chances of meeting White's challenge".

b) 7.e4 can be contested by Black with 7...b5 or 7...c5, but

7...Bg4 clearly seems to be best, and now follows 8.Bxc4. Now

8...Nh5 9.Be3 Bxf3 is strong because White has to recapture with

10.gxf3, Black replies 10....e5!, and after 11.dxe5 Bxe5 12.Qxd8

Rxd8

- diagram -

there arises an endgame with mutual chances. Ftacnik's latest

game against L'Ami was the occasion of his article and stands at

the end of the database.

One method to learn an opening/variation is to look at the games

of its leading exponent. Who this is can be easily seen in

Ftacnik's database because with 6 games (all with White) Alexei

Dreev is clearly ahead. The Mega contains more games; here the

Muscovite changes his approach and plays both 7.e3 and 7.e4. (RK)

E37 Nimzo-Indian: Sharp variations

after 4...d5

GM Hazai, GM Lukacs

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.Qc2 d5 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.Qxc3 Ne4

7.Qc2 c5 8.dxc5 Nc6 9.cxd5 exd5 10.Nf3 Bf5

Most lines

in the Classical Nimzo-Indian with 4.Qc2 lead to quiet

positional play. But after 4...d5 the positions occasionally

become very sharp; a certain degree of theoretical knowledge is

then necessary. After 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.Qxc3 Ne4 7.Qc2 Black also has

the moves 7...e5 and 7...Nc6 at his disposal, but our topic is

7...c5; then comes the more or less forced 8.dxc5 Nc6 9.cxd5

exd5 10.Nf3 Bf5, which leads to the diagram position above.

Most lines

in the Classical Nimzo-Indian with 4.Qc2 lead to quiet

positional play. But after 4...d5 the positions occasionally

become very sharp; a certain degree of theoretical knowledge is

then necessary. After 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.Qxc3 Ne4 7.Qc2 Black also has

the moves 7...e5 and 7...Nc6 at his disposal, but our topic is

7...c5; then comes the more or less forced 8.dxc5 Nc6 9.cxd5

exd5 10.Nf3 Bf5, which leads to the diagram position above.

After the obvious 11.b4 the formerly respectable reply 11...d4

has, since quite recently, to be considered as refuted (see Van

Wely-Antonio, Turin ol (Men) 2006, CBM 113).

Now the game has to focus more on 11...0-0; White replies 12.Bb2

and Black has a choice: 12...b6 immediately or first 12...Re8.

12...Ng3? instead can be considered as falling into an opening

trap, after 13.Qc3 d4 14.Nxd4 Nxd4 surprisingly follows 15.fxg3!

and White's king has "luft" on f2.

a) White can answer 12...b6 with 13.Qa4, but this seems to be

harmless. But often 13.b5 has been played, after which there

follows the piece sacrifice 13...bxc5. After 14.bxc6 Qa5+ 15.Nd2

Rab8 16.c7

- diagram -

Black again has a choice - 16...Qxc7 or 16...Rb3, in both cases

Black has a strong initiative compensating for the piece.

b) 12...Re8 prevents 13.e3, because after that 13...Ng3 14.Qc3

d4 is possible. White therefore plays 13.Rd1, after which

13...b6 14.e3 bxc5 15.Bb5 follows. White can be content with

15...Qb6 16.Bxc6! Qxc6 17.Nd4 followed by 18.Nxf5. But 15...Re6!

16.0-0 Bg4! should turn out to be a hard nut to crack. In the

only game with this sequence, Zakharstov-Loginov, St Petersburg

2002, White managed to get a draw, but Black's game can be

improved upon. (RK)

E58 Nimzo-Indian: Repertoire against

the Rubinstein Variation Part 2

GM Viktor Gavrikov

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e3 0-0 5.Bd3 d5 6.Nf3 c5 7.0-0

Nc6 8.a3 Bxc3 9.bxc3 Qc7 10.cxd5 exd5

We saw in

the first part that White gets nowhere with moves other than

10.cxd5. So in the second part the author now deals with the

main line 10.cxd5 exd5.

We saw in

the first part that White gets nowhere with moves other than

10.cxd5. So in the second part the author now deals with the

main line 10.cxd5 exd5.

Of the sideline moves only 11.Bb2 is interesting. Then Gavrikov

recommends 11...c4 12.Bc2 Bg4 13.Qe1 Bxf3 14.gxf3 Qd7, with good

play for Black.

More space is taken up by 11.Nh4, which is the old main line and

which for a long time had been considered obligatory. Actually,

Black had been doing rather well with 11...Ne7, but then it was

found out that 11...Qa5 might actually be even stronger. White

has to defend the c3-pawn, but 12.Bd2 is immediately countered

with 12...Ne4, and the continuation 13.Be1 c4 14.Bc1 Qd8 15.g3

Bh3 16.Ng2 f5 is easy to play for Black. The other bishop move

12.Bb2 cedes the control of e3, and then the setup with f3 is

more difficult.

11.a4 is also an old move, but it only became popular in the

middle of the 90s and replaced the old 11.Nh4 in popularity.

After the moves 11...Re8 12.Ba3 c4 13.Bc2, which are the most

frequently played, Black has to decide:

a) 13...Bg4 looks obvious, but after 14.Qe1 Bxf3 15.gxf3 Qd7

16.Kg2 followed by Rg1 or Rh1 White is better.

b) 13...Ne4 also has its drawbacks, after 14.Bxe4 Rxe4 15.Nd2

Re8 16.e4 Be6 the author sees some difficulties for Black after

17.e5 Bf5 18.f4.

c) 13...Qa5 also proved to be best here. After 14.Qc1 things

continue as in the line above: 14...Ne4 15.Bxe4 Rxe4 16.Nd2 Re8

17.e4 Be6

- diagram -

After 18.e5 there follows 18...Qxa4 and by perpetually attacking

the queen White should be able to force the draw. However,

Korotylev-Grischuk, Moscow 2004, riskily continued with 19.f4.

Gavrikov draws the conclusion that 9...Qc7 is a reliable weapon

for Black. (RK)